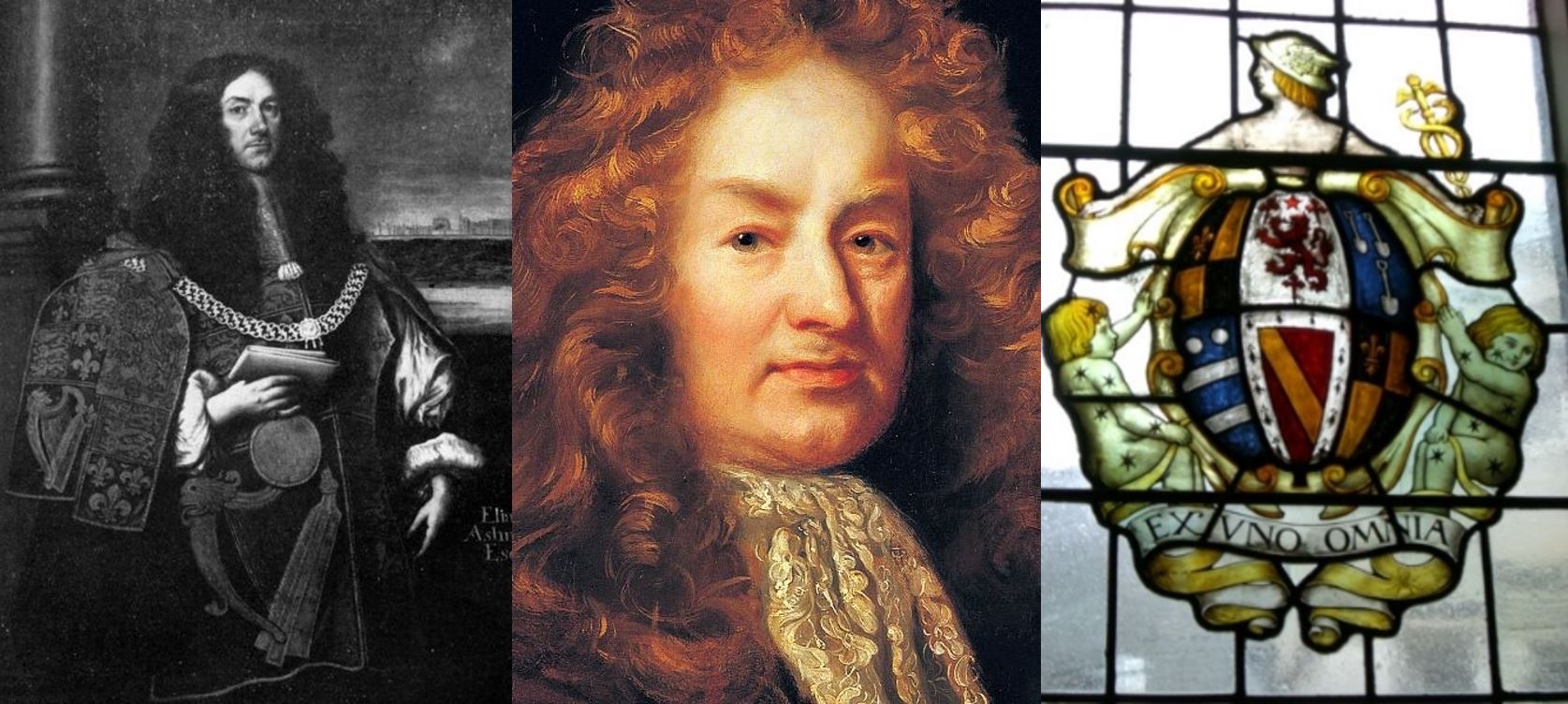

Elias Ashmole,

Founder of the Ashmolean Museum

So who is Elias Ashmole and what did he do for the Establishment

Elias Ashmole was born in Breadmarket Street, Lichfield, Staffordshire. His family had been prominent, but its fortunes had declined by the time of Ashmole’s birth. His mother, Anne, was the daughter of a wealthy Coventry draper, Anthony Bowyer, and a relative of James Paget, a Baron of the Exchequer. His father, Simon Ashmole (1589–1634), was a saddler, who had served as a soldier in Ireland and Europe. Elias Ashmole attended Lichfield Grammar School (now King Edward VI School) and became a chorister at Lichfield Cathedral. In 1633, he went to live in London as mentor to Paget’s sons, and in 1638, with James Paget’s help, he qualified as a solicitor.

He enjoyed a successful legal practice in London, and married Eleanor Mainwaring (1603–1641), a member of a déclassé Cheshire aristocratic family, who died, while pregnant, only three years later on 6 December 1641. Still in his early twenties, Ashmole had taken the first steps towards status and wealth. He also became allied with Major-General Charles Worsley (who died 12 June 1656 and was buried at Westminster Abbey), brother-in-law of his sister, Mary Ashmole, who married John Booth, of Salford.

Ashmole supported the side of Charles I in the Civil War. At the outbreak of fighting in 1642, he left London for the house of his father-in-law, Peter Mainwaring of Smallwood, Cheshire. There he lived a retired life until 1644, when he was appointed King’s Commissioner of Excise at Lichfield. Soon afterwards, at the suggestion of George Wharton, a leading astrologer with strong court connections, Ashmole was given a military post at Oxford, where he served as an ordnance officer for the King’s forces. In his spare time, he studied mathematics and physics at his lodgings, Brasenose College.

There he acquired a deep interest in astronomy, astrology, and magic. In late 1645, he left Oxford to accept the position of Commissioner of Excise at Worcester. Ashmole was given the additional military post of captain in Lord Astley’s Regiment of Foot, part of the Royalist Infantry, though as a mathematician, he was seconded to artillery positions. He seems never to have participated in any actual fighting.

After the surrender of Worcester to the Parliamentary Forces in July 1646, he retired to Cheshire. Passing through Lichfield on his way there, he learnt that his mother had died just three weeks before from the plague.

The Civil War

When the civil war broke out Ashmole, a staunch Royalist, quit London first for Cheshire, then for Oxford. In 1645 he found himself enrolled at Brasenose College, studying natural philosophy, mathematics, astronomy and astrology. The 1640s saw a great revival of interest in the occult sciences (astrology, alchemy, natural magic), and Ashmole quickly assimilated the Neoplatonic–hermetic world-view within which the occult sciences seemed to have their natural place. But astrology was more than just an occult science: it could also be used as a weapon in a propaganda war. Ashmole and his friend George Wharton found themselves providing Royalist readings of the stars to counter those given by the Parliamentary astrologer William Lilly. (Although initially political opponents, Ashmole and Lilly would later become close friends.)

In December 1645 Ashmole accepted the post of Commissioner of Excise for Worcester. Posts in the excise, combined with a series of financially advantageous marriages, laid the foundation for his future wealth. But this post did not last long: in 1646 he set out for London with the intention of joining forces with his friend Wharton to refute the ‘errors’ of Lilly. In the end, Ashmole found himself working more closely with Lilly himself: he published two translations in Lilly’s The World’s Catastrophe, or Europe’s many Mutations untill 1666 (1647), and greeted Lilly’s Christian Astrology (1647) with a poem praising Lilly as unlocking the ‘cloystered secrets’ of the ancient wisdom of the East, and thus restoring an ancient science (astrology) to mankind. Like his fellow astrologers, Ashmole was keen to defend his science against the charge of determinism: astral causes, they would usually insist, only incline but do not determine the will.

Sciences

The other occult science that fascinated Ashmole was alchemy. His first book, Fasciculus chemicus (1650), written under the pseudonym James Hasolle (an anagram) consisted of translations from the Latin of two alchemical texts, the Fasciculus chemicus (Paris, 1631) of Arthur Dee (son of the magician John Dee), and Jean d’Espagnet’s Arcanum hermeticae philosophiae opus (Paris, 1623). In his short Prolegomena to the book, Ashmole attempts to defend alchemy against the common charge that it is all fraud and imposture. There are, he insists, ‘many occult, specifick, incomprehensible and inexplicable qualities’ lying hidden in animal, vegetable and mineral substances, waiting to be discovered by the labours of the alchemist.

The years 1650 and 1651 saw Ashmole immersed in the literature, and receiving personal instruction from his ‘father’ in alchemy, one William Backhouse. This period in Ashmole’s life came to fruition with the publication of his best-known work, the Theatrum chemicum Britannicum, in 1652. (A second volume was planned, but never materialized.) The Theatrum is a collection of old English alchemical texts, in verse form, with a Prolegomena by Ashmole himself, in which he expresses his positive views of alchemy and his optimism about its future prospects.

Ambitions

Ashmole also maintained a lifelong interest in various aspects of magic, especially in attempts to make spirits appear. Here the figure of John Dee, whose ‘conferences with angels’ had caused much scandal in Elizabethan England, loomed large. Ashmole collected Dee’s manuscripts, gathered all the information he could from Dee’s son Arthur, and planned a biography of the great magician. The biography never appeared, but the figure of Dee continued to haunt Ashmole for the rest of his life.

During the 1650s, however, the focus of Ashmole’s interests began to change. Although he maintained his interest in the occult sciences, and published another old alchemical text, The Way to Bliss, in 1658, antiquarian pursuits gradually came to occupy more and more of his time. In 1655 he began work on a history of the Order of the Garter, which would be finished only as late as 1670 and published as a sumptuous folio volume in 1672. Worldly affairs also began to occupy more of his time. The Restoration of Charles II in 1660 brought an upturn in his fortunes: his known loyalty to the Stuarts made him a favourite at court, and brought him tangible rewards in the way of places and offices. For the rest of his life, he was a courtier and an official (Controller of the Excise) with antiquarian interests, rather than a serious scholar. He continued, however, to dabble in matters scientific, helping with the foundation of the Royal Society in 1660–61 and becoming one of its first Fellows in 1663. Like many other devotees of the occult sciences, Ashmole was convinced that they had nothing to fear from scientific empiricism, believing that the experimentalism of the Royal Society would only purify and strengthen alchemy and astrology.

A Wealthy Collector

Ashmole also became known, in his later years, as a great collector of manuscripts and other curiosities. His house at South Lambeth received visits from people such as Robert Hooke and Henry Oldenburg, often escorting foreign virtuosi. The collection of another antiquarian, John Tradescant, was also inherited after a lawsuit. Looking for a permanent home for these collections, Ashmole turned to the University of Oxford, offering to bequeath them to the University if it could find a suitable home for them. The University accepted the offer, and a fine new building was erected with a chemical laboratory in the basement, and display rooms above. The Ashmolean, England’s first public museum, received a royal visit in May 1683, and was opened to the public in June, with Dr Robert Plot as its first curator.

It would be all too easy to dismiss Ashmole as a mere ‘transitional’ figure in natural philosophy. Although he rubbed shoulders, in the early meetings of the Royal Society, with mechanical philosophers such as Hooke and Boyle, his own thought seems to be more akin to that of an Elizabethan magician like Dee. But this antithesis seems not to have been so clear to his contemporaries as it is to us. After all, scientists of the calibre of Boyle and Newton were prepared to take the occult sciences seriously, even to seek for ways to provide acceptably ‘corpuscular’ explan-ations of occult effects. And the idea of an ancient wisdom concealed – perhaps in coded or cryptic form – in the manuscripts of the alchemists was widely accepted even by people we like to think of as ‘moderns’. So perhaps Ashmole should not be dismissed quite so hastily as a credulous intellectual lightweight stuck in the mire of superstition.

Freemasonry

During this period, he was admitted as a freemason. His diary entry for 16 October 1646 reads in part: “I was made a Free Mason at Warrington in Lancashire, with Coll: Henry Mainwaring of Karincham [Kermincham] in Cheshire.” Although there is only one other mention of masonic activity in his diary he seems to have remained in good standing and well-connected with the fraternity as he was still attending meetings in 1682.

On 10 March that year he wrote: “About 5 H: P.M. I received a Sumons to appear at a Lodge to held the next day, at Masons Hall London.” The following day, 11 March 1682, he wrote: “Accordingly, I went … I was the Senior Fellow among them (it being 35 years since I was admitted) … We all dined at the Half Moon Tavern in Cheapeside, at a Noble Dinner prepared at the charge of the New-accepted Masons.” Ashmole’s notes are one of the earliest references to Freemasonry known in England, but apart from these entries in his autobiographical notes, there are no further details about Ashmole’s involvement.

Freemasonry or Masonry consists of fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local fraternities of stonemasons, which from the end of the fourteenth century regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities and clients. The degrees of freemasonry retain the three grades of medieval craft guilds, those of Apprentice, Journeyman or fellow (now called Fellowcraft), and Master Mason. These are the degrees offered by Craft (or Blue Lodge) Freemasonry. Members of these organisations are known as Freemasons or Masons. There are additional degrees, which vary with locality and jurisdiction, and are usually administered by different bodies than the craft degrees.

The basic, local organisational unit of Freemasonry is the Lodge. The Lodges are usually supervised and governed at the regional level (usually coterminous with either a state, province, or national border) by a Grand Lodge or Grand Orient. There is no international, worldwide Grand Lodge that supervises all of Freemasonry; each Grand Lodge is independent, and they do not necessarily recognise each other as being legitimate. Ashmole was well recognised as leading figure in the Grand Lodge in his time.

Bibliography[Hasolle, James] Fasciculus chemicus: Or Chemical Collections. Expressing the Ingress, Progress, and Egress, of the Secret Hermetick Science, out of the Choicest and Most Famous Authors (1650).

Theatrum chemicum Britannicum. Containing Severall Poeticall Pieces of our Famous English Philosophers, Who have written the Hermetique Mysteries in their owne Ancient Language (1652); repr. with an Introduction by Allen G. Debus as no. 39 in the series Sources of Science (New York, 1967). The Way to Bliss. In Three Books (1658). Source: Wikipedia |

Born:

23 May 1617, Lichfield, Staffordshire, England

Died:

18 May 1692 (aged 74), Lambeth, London, England

Occupation:

Antiquarian, Politician, Officer of arms, Astrologer and Alchemist

Other Relevant Works |

|

Lilly, William, The World’s Catastrophe, or Europe’s Many Mutations untill 1666 (1647). Contains two translations by Ashmole of astrological works. The Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter (1672). Further Reading Josten, C.H., Elias Ashmole (1617–1692). His Autobiographical and Historical Notes, His Correspondence, and other Contemporary Sources Relating to his Life and Work, 5 vols (Oxford, 1966). |

Andrew Pyle

|